Latest Red List update means 24 tortoises and freshwater turtles in Southeast Asia are now listed as Critically Endangered

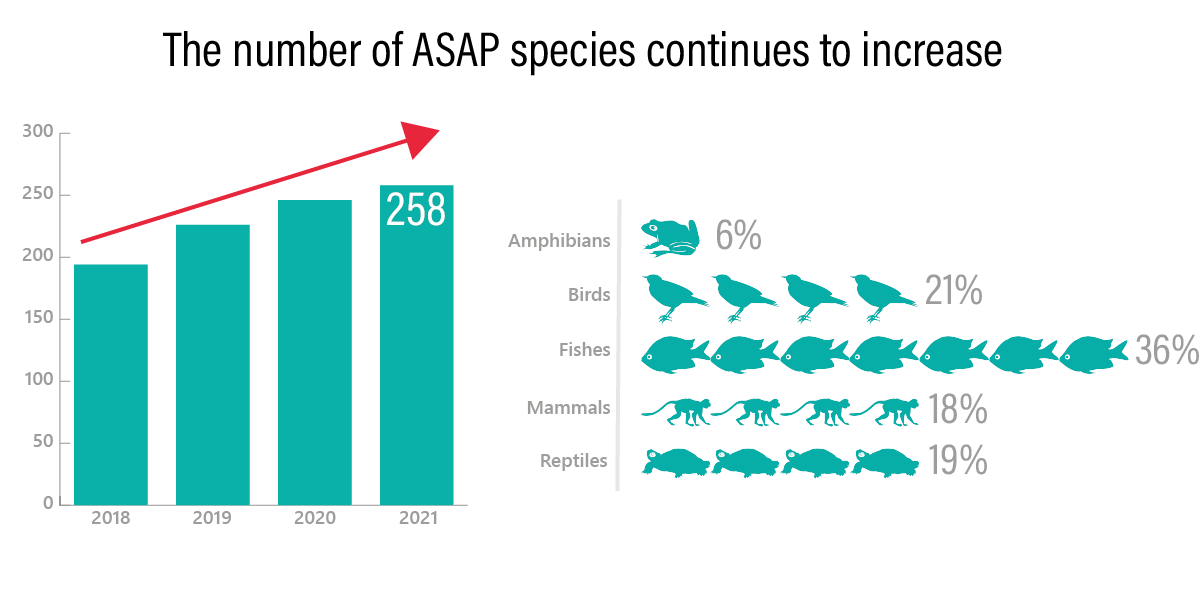

The recent update to the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM saw five freshwater turtles in Southeast Asia newly listed as Critically Endangered. These latest assessments bring the total number of Critically Endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles in the region to 24. In addition, there were seven freshwater fishes newly assessed as being on the brink of extinction. This brings the total number of ASAP species to 258.

Why are tortoises and freshwater turtles in trouble?

The primary threats that tortoises and freshwater turtles face in Southeast Asia are from trade and habitat loss. Tortoises and freshwater turtles are used for food and medicine and are farmed by the hundreds of millions to feed this demand, and there are groups that raise the question whether some turtle farms are supplementing their stock with wild-caught species. Demand for tortoises and turtles as pets is also growing. Many species are sold for large sums, particularly various rare species which are prized as status symbols.

A 2020 report by TRAFFIC, ‘Southeast Asia At the Heart of Wildlife Trade’, painted a grim picture of the trade situation. It analysed illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade across the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), looking at both live animals and wildlife products. According to historical legal trade data, 10 million wild-caught tortoises and freshwater turtles were exported from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand in the late 1990s, showing the sheer magnitude of the industry. The nature of the trade, with so much taking place illegally, means it is likely that these statistics are just the tip of the iceberg.

On land, freshwater turtle habitat is being converted for agriculture and logging, or sometimes for urban expansion. River habitat is also dropping in quality, being polluted by agriculture and industry, having its flow dynamics and bank habitats altered by dam construction, other infrastructure projects and increasing boat access.

The Burmese Peacock Softshell Nilssonia formosa is one of the species that is sadly now an ASAP species. This slow-growing turtle has an estimated generation length of 30 years and is endemic to Myanmar, where it is found in only two river systems: the Ayeyarwady River including its tributary the Chindwin River, and the Sittaung River. The species was traded in the East Asian food trade but is now rare in the wild with only sporadic encounters. Besides being traded, the riverside habitat where the species lays its eggs is changing due to high boat traffic, increased sedimentation, harmful fishing methods and gold mining impacts. Even if the illegal trade can be brought under control, these habitat changes might inhibit the species’ recovery.

“Turtles and tortoises continue to be among the most threatened vertebrate groups in the world, with over 50% ranked as threatened with extinction, a fact underscored by the recent additions to the IUCN Red List.

But there is cause for optimism: many chelonians respond well to intensive conservation measures such as nest protection, head-starting and captive breeding. We know that we can build their numbers up in captivity- rapidly in some cases such as Asian River Terrapins (Batagur) – but our ultimate challenge is to get them back into functioning ecosystems. Sadly, this will not happen until we can get a handle on the illegal wildlife trade.”

Rick Hudson, President, Turtle Survival Alliance

ASAP Partners conserving freshwater turtles

There are over 170 ASAP Partners, and many of them are dedicated to reversing the downward trend for Southeast Asian tortoise and freshwater turtles.

Protecting terrapin eggs in Northern Sumatera

Just one of the projects that ASAP is supporting through a small grants programme is to conserve Painted Terrapin Batagur borneoensis in Karang Gading–Langkat Timur Laut Wildlife Reserves, Province of North Sumatera. The species was once abundant in the area, but the population has declined sharply as the eggs of this species are collected and consumed by local people, as well as wildlife like wild pigs and lizards.

The Satucita Foundation aims to save and hatch as many Painted Terrapin eggs found during the nesting season as possible. Nest patrols will walk the two main nesting beaches of the wildlife reserves two times every night. When nests are found, the patrols will take the eggs to the safety of a temporary hatchery until they hatch, where hatchlings will be raised and later released. This expands on a highly successful program in Aceh Province, Sumatra, where more than 3,000 young Painted Terrapins have been released into the wild in the past ten years, supported by the Turtle Survival Alliance and partners.

Reintroductions on a small Indonesian island

The Rote Island Snake-necked Turtle Chelodina mccordi is endemic to Rote Island, part of the Lesser Sunda chain of islands of Indonesia. This striking turtle has been driven to the brink of extinction by the relentless demand from the international pet trade. At the same time, much of Rote island’s turtle habitat has been converted from natural wetlands to rice fields. This Critically Endangered turtle has now not been seen in the wild for more than a decade.

To secure the future survival of this species, organisations including the ASAP Partners the Wildlife Conservation Society, Wildlife Reserves Singapore and Turtle Survival Alliance are establishing assurance colonies. While this is happening, they are engaging with relevant government agencies to identify suitable reintroduction sites. They plan to repatriate and reintroduce colonies soon, working across as many places as possible to increase the chances of the species’ survival.

A global spotlight puts the focus on ASAP species

It is not often that an ASAP species gets global media attention, but that’s exactly what happened in January this year when the New York Times ran a piece about the Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle Rafetus swinhoei. When one of the last two known remaining individuals, found in a Vietnamese lake was confirmed to be female, it made a big splash. Alongside a male at a Chinese zoo and two other promising leads, the discovery gives hope for the future of the species, widely regarded as the most endangered turtle in the world.

The organisations leading this work (including the ASAP Partners the Wildlife Conservation Society, the Turtle Survival Alliance and the Asian Turtle Programme) achieved a level of media coverage rarely seen for freshwater turtles and have helped to raise awareness about a relatively unknown, yet highly at-risk species.

Featured image: Wildlife Reserves Singapore